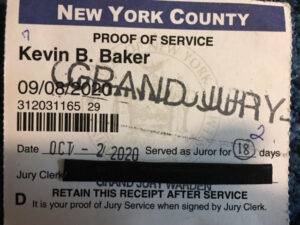

The summons arrived in August: I was to serve on one of the first two grand juries convened in Manhattan during what now looks to have been the Covid “hiatus,” that brief lull in the summer of 2020 between the worst waves of contagion and death. What my fellow jurors and I would get in return was $40 a day—and a look inside a criminal justice machine that kept cranking on imperturbably, through pandemic, riot, and economic collapse, just as it always has.

Grand Jury No. 2 was assembled the day after Labor Day, in a big, musty room at 130 Centre Street, in the heart of New York’s courthouse district. We maneuvered cautiously around each other even in the big room, masks in place, eyes a little apprehensive as we took our socially distanced places. We were each asked by name if we were ready to serve for the next four weeks on a grand jury or not. Those who said they would like an exemption—about half of us, from what I could tell—were told they could talk to a judge, but warned that even if they got off this time they would probably receive a new notice summoning them to appear four months later.

A grand jury is not like regular or “petite” jury service. It’s not where you determine whether a mugging or a car theft or a murder has been committed beyond a reasonable doubt. It’s not where you find the landlord liable for that puddle of water someone slipped on in the lobby. It’s not where you judge anyone at all, really. It is, instead, where you determine “whether there is legally sufficient evidence of a crime and whether there is reasonable cause to believe that the accused person committed that crime.” That is, to believe that “something happened,” as we came to describe it to ourselves in the jury room.

As such, grand jury service is much harder to get out of than regular jury service. There is no voir dire,no process in which your presence might be challenged by attorneys from either side because of what you do for a living, or your mostly deeply held beliefs, or because you’re trying to act crazy.

I went willingly. I had served on juries in both criminal and civil cases before and found the experiences, respectively, sad and more than a little annoying. But this, I was sure, would be different—participation in a critical part of our civic duty.

Grand juries date back to at least 1166 in England, and were originally designed to extend the power of the king. By the 17thcentury, though, they had evolved into a civil liberty. Your right to a grand jury, in the case of “a capital, or otherwise infamous crime,” is guaranteed under the Fifth Amendment. In New York—and in 17 other states—every felony charge must be presented to a grand jury, and you cannot be brought to trial if it does not return a “true bill” of indictment. (A refusal to indict is known, believe it or not, as an ignoramus: literally, “we ignore it.”)

In America, grand juries have wielded real political power at times, and considerable independence. Romanticized as both “the shield and the sword” of the law, they have been used as a weapon of last resort when the justice system itself has appeared hopelessly corrupted or stymied. In the past, grand juries have issued investigative reports that exposed crooked cops and political bosses, criminal syndicates, and corporate lawlessness. I had no illusions that we would be doing anything that spectacular. But I did harbor fantasies that we might bring down networks of scheming, white-collar criminals—maybe even some minor Trump relative, engaged in who-knows-what skullduggery.

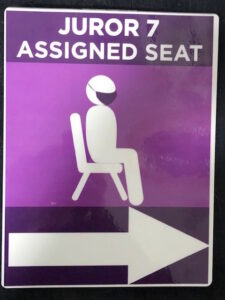

No such luck. Once the 23 members of our grand jury were assembled, we were escorted across the street to another courtroom at 111 Centre Street, a less massive, more faceless courthouse. Here was where we would spend most of our time, 10-5, Monday through Friday, for the next month. Grand juries rarely sit for more than two weeks, but we were informed that we would have to serve longer, “to clear up the backlog”—a backlog comprised almost entirely of drug cases.

In New York City, nearly all drug cases, from all five boroughs, are coordinated through the Special Narcotics Operations Office in Manhattan. What this meant in practice was that an undercover officer—a “u.c.,” in the pervasive jargon of the courtroom—would describe making as many as eight-to-ten drug buys of maybe $60-$100 each, over the course of as many weeks. In the exact same way, and from the same dealer on the same street corner.

After the u.c. had testified, we would hear his or her superior officer affirm how he had “vouchered” the drugs from each of these buys, complete with voucher number. Then either a lab tech or the presiding, assistant district attorney (ADA) would read out the lab reports affirming that each of these buys had indeed been found to be heroin or cocaine or crack cocaine or methamphetamines or fentanyl.

The tedium of this is nearly impossible to describe.

The conditions we worked in only added to the monotony. The court system, to be sure, had gone to great lengths to shield us from the coronavirus. Aside from the police and the prosecutors, our grand jury seemed to be the only people in the entire, ten-storey courthouse. The other courtrooms and the offices on our floor, at least, were locked and darkened; in a Kafkaesque touch, we took to idly trying the doorknobs during our breaks and lunches. They never opened. Only three people were allowed inside an elevator at a time, but when you pressed the button for the cars they appeared instantly—and always empty.

In our chilly, windowless courtroom, we were required to wear our masks at all times and seated just one or two to a bench, though we did not sit for very long. Growing up, I was forced to listen to hour-long sermons in an evangelical church, but I can tell you that the benches of the Manhattan Civil Courthouse are far and away the hardest, most uncomfortable surfaces I have ever sat on. We had to constantly get up and stand around the back of the room just to relieve the numbness in our legs and backs. (Only too late did it occur to us to wonder if the air being filtered in to us was actually safe.)

The witnesses, the ADAs, and the court officers were all ensconced behind plastic barriers so thick that the court stenographers had to ask witnesses or lawyers again and again to repeat what they had just said. Before each new witness could testify, a cleaning woman entered to scrub down the entire witness stand. The witness then sat down, donned a face shield, lowered his or her face mask, unwrapped what we came to call a fresh “mic condom”—a small, brightly colored rubber cap—and placed it over the microphone.

The conditions aside, it is the broken narrative of the grand jury system that wears you down. The presentations of evidence do not resemble real trials, much less the legal dramas or the cop shows you see on TV. The accused are allowed to testify on their own behalf but their attorneys are not allowed to say anything to anyone, so they almost never appear. The entire month we were on duty, through 75 separate cases, we never saw a defendant or a defense attorney.

The ADAs do not strive to establish some clear picture of the case at the outset—far from it. They are really not supposed to, lest everything bog down interminably. Thus we sat like Plato’s cave dwellers, trying to judge reality by the rough pantomime we saw of the outside world—listening to loose shards of the government’s story trying to piece together what had gone on. For the first few days, we peppered the ADAs with questions: Why were the police suspicious of this person? Was a warrant obtained for that apartment search? Was this part of some other, bigger operation?

None of that was relevant, we were told. All of that would be decided at trial—if any of these cases ever went to trial. All we were there to decide was: Did something happen?

Yes, something happened.

After a couple days, it nearly impossible to still pay much attention during these interminable presentations—which was perhaps the point. It is one thing to read about how the war on drugs is conducted. It is another to experience it in action, day-by-day, for a month.

The ADAs were mostly young and often inexperienced. The court officers announced, at different times, that two of them—both young women—had just presented their first cases, and when they did we applauded and both attorneys blushed with pride. The undercovers, by contrast, had often been at this a surprisingly long time, a couple of them for 20 years, one for 28 years—well past the point of being able to retire with a full pension. It seemed almost inconceivable: twenty years or more of hanging around New York street corners, scoring yet another vial of crack or a glassine envelope of heroin.

There was also a color line. The u.c.’s were overwhelmingly Black or Hispanic; the ADAs, all white, save for a couple of Asian-American women. The cleaning lady: always Black.

For all that our services were supposedly needed to clear up “the backlog,” the whole process was woefully uncoordinated. Over and over again, cases were continued or delayed because the undercover was still “across the street” in another court building or, presumably, out scoring still more drugs and making the next case. When they did arrive, the cops, for all their experience, rarely seemed prepared. They gave their testimony in low and grudging voices as if they had never done this before, referring constantly to their “buy sheets” to refresh their memories, until it was obvious that they had not so much as looked at the casework before getting into the witness chair.

Once they did open their mouths, out poured all the bureaucratic jargon of their world. We heard about “bundles,” and “twists,” and “wholes,” and “D”; of the SOMU, the DEFT, the DCJS, the VCS, SNEU, CEU. Suspects were identified first by their “J.D. names”—their “John Doe names”—before their real identities were revealed. One undercover detective could not remember her suspect’s real name and could not even find it on her buy sheet, which threw a monkey wrench into the whole machine—for a little while. We were not about to indict anyone without an actual name!

It was, nonetheless, hard not to sympathize with the undercovers. It must take considerable courage to get into a car or go into the apartment of a well-armed drug dealer, particular for the smaller, women u.c.’s. The pushers they arrested were always selling hard drugs. No ADA so much as tried to indict anyone for selling marijuana, and whenever a u.c.’s report mentioned pot, we were specifically told to ignore it.

Who wants to live on a block full of drug pushers? But where was the end of it all?

In between all the drug busts, we did get to hear other cases from time to time. These were even promised to us as a “break” in the monotony, and at first we welcomed them as such. There were gun possession and gun sale charges. Bail jumpers, and registered sex offenders who, after years of reporting in as required every month, suddenly stopped showing up. Violence, in nearly all its forms—though sometimes the crimes could be funny, even hilarious.

A pair of female rental-car employees who decided to go on a joyride with their boyfriends during their lunch break, and ended up getting into a brawl and pulling a gun on father-and-son construction team they had cut off and then showered with obscenities, in the time-honored New York way…A man who meets a woman in a hotel room in yet another version of the old badger game—and remained, still hoping to get lucky, even after he realized she was trying to drug him…A drunk who insisted on joining a late-night soccer game in Central Park, lost his wallet, then insists he had been robbed and begins shooting a gun wildly at his fellow players as they fled…

Yet as we went on, it all became less and less funny.

“Attempted strangulation” of a peace officer when she stopped a deranged man trying to bolt into Harlem Hospital…“Attempted murder” by a woman who brought a knife to her girlfriend’s apartment and stabbed her five times in the back…A young woman professional who sobbed uncontrollably as she described how an intruder had pushed his way into her East Harlem apartment and robbed her, beat her, attempted to rape her—the experience still traumatizing her, still ruining her life, as she put it, over a year later…

The endless supply of guns, the thin layer of civility and how easily it gives way to frenzied, mindless violence in this, our city. The courage of the victims in resisting, healing, or simply enduring all so overwhelming that soon we found none of it very funny anymore, even the most ridiculous episodes.

After a few days we began to bond as a group. People brought in baked goods and bundles of Halloween candy, as if we were in any other office, at any other time. Mike, the warden of our jury—fittingly, the official title—was a public servant in the best sense of the words, a fastidious but friendly individual who was quick to grant us a day off when we needed one, and always got us home early when the system backed up again. Chris, another jaunty warden with a pair of handcuffs constantly dangling from his belt bounced in and out of our courtroom, always with the good word on his lips. You could almost see the sitcom character roles being assigned: the jolly juror who sat up close to the ADA and invariably had a quip at the ready. The pretty young blonde woman who was chosen as our foreperson, and got stuck with the job of reading the oath to each witness. The diligent young woman executive who served as secretary and thus got stuck with the job of keeping track of each vote. The cancer research scientist who sat in the back loudly complaining about how this was all a waste of his time.

It was hard to argue with him. The $40 a day we got for our services was less than half the minimum wage in New York State. We were banned—by state law—from getting subway fare, not to mention “lunch, parking, babysitting, etc.”

Some of us simply opted out. I noticed that two of my fellow jurors were not voting at all, and quietly asked them about it, wondering if their actions constituted some sort of political protest. But no. One of them, a neatly dressed, middle-aged man with close-cut hair, turned out to be a retired cop, furious that he was required to be there. He showed his displeasure by openly reading a book on the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg throughout the proceedings. The other was an Asian-American woman, maybe in her forties, who said she had told the judge that she didn’t have enough English to understand what was going on. She was placed on the grand jury anyway.

It was hard to blame anyone for abstaining for any reason. For all of us, as the endless drug cases ground on, our attention strayed, our eyes shifting surreptitiously—then openly—to iPhones, newspapers, books. No one objected to this. Before two weeks were out, the ex-cop vanished, without explanation. So did two more of our fellow jurists. But the rest of us went on, still voting indictments.

A man in Tompkins Square Park whose face was sliced open with a boxcutter in an argument over a woman. The suspected assailant eventually arrested by an officer who was already inthe park—guarding a statue of former Vice-President Daniel L. Tompkins…A man who shoved a jeweler to the sidewalk in the Diamond District and grabbed his box of gems. He was stopped by a passing driver—who got his head cut open for his troubles…A retired UPS worker in Harlem, waiting for his wife to return to the car with their takeout dinner, who was jumped by a deranged young man demanding he drive him to Brooklyn. The former UPS man wrestled the lunatic to the ground, tearing up his knee in the process, while yelling at onlookers to get a cop. “But they just kept taking video with their cellphones,” he says in a voice somewhere between exasperation and despair…

At lunch we got to go outside, to sit in the sun and eat in the public spaces around Foley Square. Had we all been forced to use the cramped jurors’ lunchroom we could not have kept at a proper distance from each other, but it was “The Edge”—that late summer moment in New York when the weather is neither one thing or another, neither summer nor fall, and we could eat outdoors. Right outside our courthouse was a sweet little pocket park that had become a homeless encampment. Thomas Paine Park, a couple blocks away in Foley Square, was less out of control but it was also filthy, with uncollected trash strewn through the grass.

We wondered if this was part of the police “slowdown” that was rumored to be going on in reaction to the Black Lives Matter protests that summer. The cop unions denied it, and the officers guarding our courthouse were unfailingly polite, even holding doors for us. But they looked on with apparent disinterest at the homeless men raging and shoving at each other a few feet away. Nobody seemed to care. Down in Copland, in the very heart of government, government seemed to have all but abdicated its role. The only continuing function, it seemed, was its first priority: to keep the buy-and-bust, indict-and-jail machinery going.

As our tour of duty went on we noticed that more and more of the busts had taken place since the pandemic started, then just a few days before. So much for ending the backlog. We began to realize that there is always a backlog.

In the more extended set-ups, the undercovers bought hundreds, even thousands of dollars worth of drugs over the course of months—in one case, nearly $14,000. We weren’t allowed to know why this was, much as we speculated on it—To set up some bigger dealer? Work their way up to the cartel leadership? But Pablo Escobar was not being indicted.

“It’s more sideways,” veteran criminal defense and civil rights attorney Alan Rosenthal, told me a few weeks after my time on the jury, describing the direction in which drug cases are more likely to move. “What is pretty standard fare is busting the person, and then putting the squeeze on them—‘Do you have information to sell, out of prison?’ Whether they can legitimately finger someone or not is almost beside the point.”

That assessment is largely confirmed by figures from the New York State chapter of the Drug Policy Alliance (DPA). When it came to the higher levels of arrests for drug dealing in the city in 2019, there were only 646 arrests for the “criminal sale of controlled substance” in the third degree. In the second degree, there were only 84 arrests, in the first degree—the level at which we might actually be talking about drug kingpins—just 16 arrests.

That’s out of 21,612 total drugs arrests made in the city in 2019. It’s a figure, to be sure, that is far below the 98,591 arrests made in New York City in 2010, before the notorious Rockefeller Drug Laws were finally reformed—though that figure included thousands of marijuana arrests (Though pot has been largely decriminalized, the NYPD still issued 15,000 misdemeanor summonses for pot in 2019, and made about 1,000 arrests for cannabis.).

So what is going on?

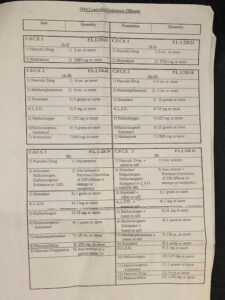

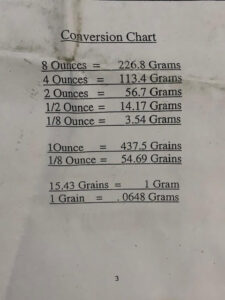

The answer lies in the seven-page handout my fellow jurors and I were given at the start of our service, a document obviously copied from copies many times, listing 83 separate “controlled substance offenses” by drug, type of drug, and amount, along with a handy “Conversion Chart”: 8 Ounces=226.8 Grams…1 Ounce=437.5 Grains…15.43 Grains=1 Grams…

The idea of all these repeat buys over so many weeks and months is to collect enough heroin or crack or fentanyl to make a felony case. What that does for the communities these busts are supposed to protect is unclear. So is what happens to all the cash shelled out by u.c.’s. How much of it is spent on the weapons that remain ubiquitous in our city—or on moving in more product? How much of it goes to those dealers who are arrested on other charges—or who flee, or are killed, or simply leave the life before they’re busted?

It is impossible to delineate exactly what New York City spends on drug busts, but the DPA estimates that the NYPD’s share was about $150 million in 2019. At the same time, the budget for the Special Narcotics Prosecutor’s Office was $22.8 million for 2020.

Not that these figures come close to the cost of enforcing our drug laws. In 2018, for instance, a total of almost $31.8 million in “criminal assets” was seized throughout New York State, under state and federal forfeiture laws. These might include a drug dealer’s car—or his grandmother’s house—and are “essentially another way of pulling a lot of resources out of communities of color,” according to Melissa Moore, New York State Director of the Drug Policy Alliance. Then there is the estimated $60,000 needed to jail every state prison inmate for a year. And there was the cost in time, as Alan Rosenthal points out, “if you’re measuring police time, and court time, and then you threw in sentencing time.” Not to mention all of our time, together in the grand jury room.

Is all this too much to spend on busting drug dealers in a city that has seen a sharp increase in crime? It would be a ridiculous exaggeration to say that the money the prosecutor’s office pumps into the drug trade in New York is what keeps it going. Yet as we all know from Economics 101, the churn of money is always vital. During the time of Covid, especially, it must have served as its own little government stimulus—a subsidy of sorts for drug dealers.

Unsurprisingly, drug arrests in New York include a disproportionate number of the poor—and therefore people of color. Some 43.7 percent of all drug arrests in New York City were African-Americans in 2019; 39 percent were Hispanics. No doubt, all these endless drug busts are supposed to protect those same Black and Hispanic and poor neighborhoods. But if this is really the intention—if it’s really so important to get these dealers off the streets—then why leave them on their corners for six or eight or ten months?

In the hallways, on our breaks, my fellow jurors and I debated alternatives. Daoud, a big, good-humored electrician for the MTA, thought full legalization of drugs was the only answer. Our cancer research scientist, still loudly impatient to get back to his work, just wanted to abolish the grand jury system, period, and turn indictments over to a panel of judges. Someone else suggested more open policing, a proliferation of uniforms instead of u.c.’s around our most drug-ridden neighborhoods, so they could be kept safe and open for their vast majority of law-abiding residents. But after so much conflict over police abuse this year, how much trust remains to make this a possibility?

Even the passing glance my fellow jurors and I had into the system told us that reforming it, and reallocating the resources should be inescapable. Yet at the same time, we had to acknowledge that simply stopping this gigantic, perpetual motion machine of buy-and-bust, impoverish and imprison, won’t bring on the beloved community. “Defunding” or “abolishing” the police won’t change the fact that our values as a society are badly warped, that we are everywhere bent on the quick fix and the quick payoff; our mentally ill left to fend for themselves, our poor ignored or abused, our first resort to any frustration or insult too often mindless violence.

Of course our police, and the officers of the court, and all those fresh-faced young assistant D.A.’s, and all the other living parts of this machinery subject us to this fragmented narrative because that is what they live with, day in and day out. The city, to most of them, cannot be anything but a place of senseless violence and indulgence, to be swept up around the edges and taped back together for another day while they go back to their homes in other boroughs and other towns and communities that make sense to them. Of course the idea that anyone should challenge their authority in holding back the chaos fills them with indignation. Of course the idea that they might be helping to perpetuate it is not something they can ever consider.

No one wanted our opinions on anything like this in the grand jury room, of course. Just our hands raised to send another case—another human being—spinning its way through the system.

We indicted everyone, returning a “true bill” on all 75 cases we heard, with very little deliberation. There were 23 of us on Grand Jury No. 2, at least to start—the traditional number, also going back centuries in English jurisprudence—and only 12 votes needed for an indictment. There was remarkably little disagreement, even though we pretty much reflected the diversity of our city: seven Black people, at least three Hispanics, two Asian-Americans, women and men almost evenly divided, young and old, drawn from many different walks of life. All of us voted against a charge here or there, but there was never an overall votenotto indict. Never an ignoramus.

Could we have done more?

From what I’ve determined since my tour of duty, as grand jurors we possessed powers—at least in theory—well beyond what we were told in the courthouse. We could have asked any questions we wanted to of the witnesses before us, or even tried to subpoena new witnesses on our own volition. But I honestly don’t know how much would have changed had we known this at the time. The sheer boredom weighed heavily against any desire to extend anything and many of us still had to go home and work for more long hours at the end of the day.

At the end of our service, my fellow grand jurors and I tapped elbows and said our goodbyes through our masks, and headed off to our subway stops through the early October sunshine. As I walked to the west through Tribeca, I noticed that the streets were largely denuded of people, but that workmen swarmed over one building after another: new skyscrapers that seemed to defy the laws of physics. Converted factories, gorgeous, high-ceilinged, cast-iron stores and buildings being converted into luxury residences where some of the very richest people in the world will live, or at least land-bank. The city readying itself to open up again and go right back to how we lived then, before the Covid, with people and neighborhoods such as these encased in splendid isolation from the endless, daily buy-and-bust-and-bag going on so near to them.

We’ve all heard that doing the same thing the same way and expecting different results is the definition of insanity. But what is it when a society does the same thing in the same way, over and over again, decade after decades, with no good results…and expects nothing at all to change?