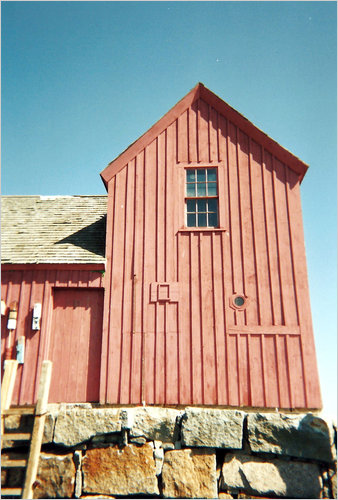

The Bakers’ home, left, and Main Street, right, presided over by a church that residents call the Old Sloop.

I grew up in a small town called Rockport, on the north shore of Massachusetts, home to no more than 5,000 people when we first moved there, and dear to those who know it. It is a place of rugged natural beauty: a shore of granite outcroppings that jut into a cold blue sea, a movie set of a New England village with streets full of small shops and not a traffic light in the town.

My mother was so happy when we moved there from New Jersey that she used to make up songs about it and sing them as she literally skipped down to the ocean. It was a place she would always love more than anywhere else on earth, and it was easy to see why. For most of my childhood we lived, very cheaply, in a two-story, wood-frame house, with a yard full of trees and a wood behind us. We ate wild blackberries straight from the bushes that grew along the edge of our backyard, spent the summers swimming in abandoned granite quarries and skated over their black-green depths in the winter.

The town was almost unbelievable in its innocence, its sweetness. Rockport Junior-Senior High School, with 250 students, was too small to have any serious cliques and divisions; the same kids starred on the basketball team and in the school play. There weren’t even any locks on the lockers; no one ever thought to put them there. Little League games weren’t laden with adult expectations. Our champion Pigeon Cove Red Sox were coached by a couple of hippie-ish high school kids who piled us all into their old wrecks after each game to get ice cream.

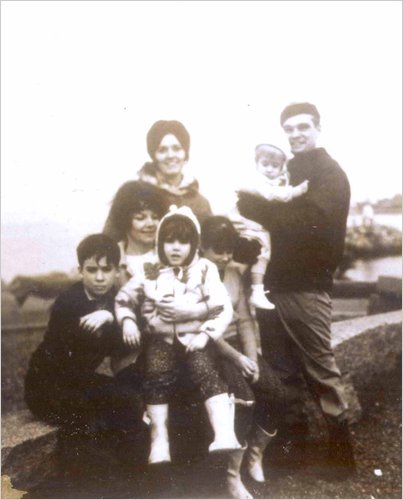

The author, far left, next to his mother and two sisters. His father is at far right with two other relatives.

Yet Rockport wasn’t merely quaint. It was a real place, a community in balance with itself that provided guideposts to a wider, adult world for its young people — including the way out. As a boy, I explored them all, pedaling my bike between Toad Hall Bookstore and the public library, both built from the town’s own granite. I learned to write professionally at the town ball field, next to the railroad yard, with its Victorian turrets flanking the grandstand, its wooden scoreboard and a tricky hill that toppled many a visiting right fielder. I made $10 a game — a fortune in 1972 — as a 13-year-old stringer for The Gloucester Daily Times, but I had to learn to type to keep the job.

I also took the train — the literal way out — to meet my father in Boston for our annual visit to Fenway Park. It was a branch of the old Boston & Maine Railroad then, with dark, grimy cars and immensely tall, heavy seats covered in green patent leather. Outside passed towns with names that I had never heard before, and it seemed like a very big adventure.

Yet as I got older, nothing enthralled me as much as the Little Art Cinema. It was a repertory house, run out of the second floor of a Scandinavian-American meeting hall, and it looked like something from a set of “The Music Man.” There was a small stage, a velvet curtain and a piano in one corner, as if the room were used for recitals or awards ceremonies, which it often was. It featured old classics and “art films” that were hard to find outside of a major city. There I saw any number of wonders for the first time: Chaplin and Keaton silents! Fellini! Ingmar Bergman!

It was not just the films, but the sense of a greater world they conveyed. They did this in New York City, I knew, sat and watched films with subtitles and talked about sophisticated things. I wanted to be there.

I did leave for the city, and for college, as did most of my classmates. Small towns should send most of their young people away; that’s how it must work. I always came back to visit, usually around Christmas and a few days in the summer. As the train drew near, I would eagerly anticipate seeing again the old, shingled New England houses, with a flag over the door and a pile of lobster traps on the lawn. I would imagine the feel on my bare feet of the stone path up to the highest jumping rock at Pine Pit — a path that I could have traversed blindfolded, and still could.

But things changed, as they will. No place is so idyllic as to keep out the exigencies of life. My parents divorced and our house was eventually sold. Both my sisters left, married and made homes for themselves in other places. My mother never would leave willingly, but she succumbed to Huntington’s disease, a terrible degenerative illness of the brain, and in 2005 had to be moved to a nursing home a few towns away.

Not long after she left, I again returned to Rockport by train — it was a clean commuter line now, its grime and green patent leather both gone — to wrap up a few details with her lawyers. The station had always been a place of joyous greetings and tearful farewells, but now there was nobody to greet me. It was late in the year, and though it was not yet 5 o’clock, it was already dark. I made my way to the bed-and-breakfast along a street that ran above a park and a pretty little brook. I had known that street since I was 9 years old, but there were no streetlights on and it was pitch black. For a moment I felt completely blind, guided only by the sound of the running water.

I had moved away many years before. But for the first time, I felt like a stranger in my hometown.

I found the bed-and-breakfast, a charming little place called the Inn at Seven South Street that was where my parents had stayed when they first came upon the town in the 1950s. Later that night I went to my old movie house. It hadn’t changed much. “The Grapes of Wrath” was playing and show times were still at 7 and 9. You still bought your ticket at a tiny cashier’s window on the first floor. I could remember well waiting there with my friends for the first show to let out, maybe provisioned with a bottle of Twin Lights grape tonic, trying to read the faces of the people coming down the stairs. There were neighborly, joking exchanges: a couple of voices calling out, “Any good?” and others replying, “Oh, you’re wasting your money!” Then it was your turn to go up the carpeted stairs, into a room redolent of wood and leather seats, and see a new world open up.

This evening, for some reason, the heat was not working, and the small crowd soon thinned out. By the end, I was the only person left, shivering as I watched the Joads’ truck go down the road. When it flickered out of sight, I made my way back through the dark streets and fell into a deep sleep.

My mother moved from one nursing home to another as her condition deteriorated — as we knew it would. By the end she could still recognize us, and say a few words, but now she spent most of her days in a wheelchair, her head down and her limbs twitching, talking compulsively to herself until her voice was a raspy whisper. She died last spring.

On Christmas Eve my sister Pam and I decided to attend the candlelight service at the Old Sloop, the Congregational church where we had gone as a family. I arrived early and strolled up Main Street looking for some place to kill a little time, but everything was closed, as it would be that evening. I had friends who lived in town still, some of the best friends I will ever have, but I could hardly impose on them without notice on Christmas Eve.

Rockport itself looked as pretty as ever. Tourists still flocked to its beaches and to Motif No. 1, the red fishing shack that is a favored subject of countless painters. All the places I loved growing up were still there, and I knew I would come back to visit again. But with my mother gone, with my family and our house gone, it could not be the same. Rockport, as a good town should, showed me the way out when I was young and I seized those invitations. For all the years I lived somewhere else it remained my own, much as you can put some beloved object away and take it back out whenever you choose. But now, with my family gone or scattered, it could not be so easily retrieved.

Kevin Baker is the author of the novels “Dreamland,” “Paradise Alley” and “Strivers Row.”