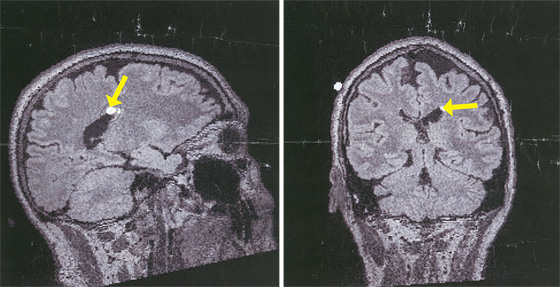

Baker’s Brain Highlighted at left is an abnormality that proved benign (the brain disease he did not have); at right, the caudate nuclei, where his brain is likely to shrink first.

(Photo: Courtesy of Kevin Baker)

A couple days later, the bottom fell out. I was working at my desk when I began to doubt every single thing that I was writing. I was certain that I was already losing my ability to think, to put together a simple sentence. Later that night, lying in bed, I was gripped by a terrible, souring sense of dread, a feeling that everything in my life was useless, meaningless. I had never experienced anything like it before. I am a person of faith and optimism, at least when it comes to my personal outlook, but all that gave way before this wrenching, physical sensation of despair. This feeling came over me several more times during the week after my test. Nothing, not even the most soothing and optimistic thoughts I mustered, could ameliorate it. I wondered if this was what true, clinical depression felt like.

Then it would fade away and I would feel strangely exhilarated, just as one does when a fever passes. I learned to ride these moods out, just try to get through them, and soon they largely disappeared. I was, I suppose, building a new wall. All that brave confrontation, just to escape behind a new layer of denial! Nonetheless, everything did seem more intense, more edged. My moods were more mercurial, I was angrier, more sympathetic, even more apathetic about things—always aware that these very mood swings, too, were symptoms of Huntington’s.

I made predictable resolutions. I would live more in the moment. I would hone my life to the essentials; read more great books; stop wasting so much time on newspapers, the latest catastrophe from Africa or China, or the op-ed pages. Who had time for it? Instead, I would write and write and write, build a legacy of work.

Yet this soon created its own sense of panic. I had easily twenty, thirty, maybe more good ideas for novels, histories, screenplays—how would I ever get all that done? What I really wanted was to live like I always did, taking little care of myself, wasting time worrying over politics, or how the Yanks were doing, or even the banality of other people’s opinions. As a novelist I learned long ago to pace myself, building something day by day, rewarding myself along the way with all the sweet distractions of modern, urban life. I wanted my trivialities. I kept thinking of the title of that self-help book, something like Don’t Sweat the Small Stuff—and It’s All Small Stuff. But of course it’s the small stuff that we crave. That’s what gives us the illusion that life is infinite, the only thing that saves us from the terror of consciousness, the root of which is that uniquely human knowledge that we are going to die. My mother’s denial did indeed make everything worse for her, and at times it tormented those of us who loved her. But now I found her stubbornness, her desire to cling to the life she had known, understandable, even admirable.

I started to tell people about my test results, what they meant. This made my wife uncomfortable, but I couldn’t help myself. I had some kind of compulsion to tell friends, family, even professional acquaintances. I wasn’t sure why I felt this need. Was I trying to solicit their pity, their admiration? See how brave he’s being!

Probably. But I think I was also doing it out of sheer incredulity, or even as a cry for help. Here I am dying. Do something!

My friends duly praised my courage—as if I had any choice. They spoke about all the great things going on in medicine today. I nodded and smiled, told them yes, I would pursue every cure. But there are no cures, at least not yet, and I doubt that a nation bent on spending three or four trillion dollars on the grand task of making the Iraqi people learn to love one another is ever going to devote much more to solving my little brain ailment. For that matter, I can’t honestly say that my disease should have any priority over the likes of breast cancer, strokes, heart disease, or any number of other maladies that affect many more people.

All things considered, I knew that I had already had a phenomenally good life. Even when it came to the Huntington’s, I had been lucky enough not to live with the disease hanging over my head. I was never somebody who worried about death or thought about it much at all. My wife and I had fortunately decided not to have children, a decision we reached more or less by inertia over the years and which meant that, thank God, I didn’t have to worry about having passed this on to someone else.

And yet, inevitably, I would find myself filled with rage at times. I thought maybe it was the knowing that made all the difference. I joked about the old Woody Allen lines, from Love and Death: “How I got into this predicament I’ll never know … To be executed for a crime I never committed. Of course, isn’t all mankind in the same boat? Isn’t all mankind ultimately executed for a crime it never committed? The difference is that all men go eventually. But I go at six o’clock tomorrow morning.”

But I wasn’t going tomorrow morning. No one is sure what triggers the onset of Huntington’s. The gene’s interaction with other genes, or environmental factors, or even aging itself may play a role. Heredity and especially gender seem to be very strong factors. The disease could begin to take its toll at almost any time, but because I inherited it from my mother instead of my father, it is more likely to manifest itself around the same age when she got it, at 65 or maybe even older—a very late onset.

“The brain copes, until it can’t anymore” is the exquisite phrase with which Herminia Diana Rosas, an assistant professor of neurology at Mass General and Harvard Medical School, describes the progress of the disease. Huntington’s may well be active in the brain ten, even twenty years before any symptoms begin to show up. We don’t see its effects because the brain rallies to adjust. In a touchingly human response to this threat, the neurons compensate by trying to do less, or by sharing vital information among each other, squirreling away knowledge and memory where they can.

In other words, I had not received some fatal diagnosis, not really. All my Huntington’s gene guaranteed was that I was going to start to die, most likely at the same age that many people start to die, from one thing or another, prostate or heart disease, stroke or diabetes or Alzheimer’s—much as we are all dying, all the time. I might have another good sixteen years ahead of me, maybe even more. I joked that it was like being on death row, only with better company. I joked that it was like being on death row, only with better food. Coming out of my agent’s building on yet another gorgeous summer day—and what a beautiful summer it was—I told myself, “You’ll be doing this ten years from now, and you’ll still have six years to go. Think of how long that is, how much will happen and how much you can do!”

What I really feared was not death but what would precede it. Dr. Hersch’s “coarseness” meant a lack of nuance—a great prescription for a writer. I would be unable to work, to organize my thoughts or comprehend the world around me. I would forget friends, names, faces, facts, memories. I would be unable to control my moods, my movements, my urges, would become a living caricature of my former self—much like what I had seen happen to my mother.

Our efforts to get her to adjust to life at her assisted-living facility were breaking down. She became belligerent if she felt she was being mistreated or thwarted in any way. She kept insisting that she wanted to be married again, kept pursuing men of any age. When someone told her that a 95-year-old fellow resident at Landmark had said she was nice, she harassed him to the point where she had to be forcibly removed from his room, slugging a female staff member in the process.

This time she was ejected from the facility. After a brief and volatile stay in a nearby nursing home, my mother was shipped out to a psychiatric ward, where she was drugged nearly to the point of being insensible. She couldn’t speak, could barely move, and seemed to be experiencing hallucinations. My sister, noticing other inmates walking around dressed in some of her clothes, raised hell, cajoled doctors, and managed to get her transferred to a much better facility, a sprawling state hospital. It was a place with light and space and a dedicated staff that adjusted her medication so that she was alert and talking again. She seemed much happier, the violent rages ebbing away, but all the transfers, and the progress of her disease, had taken its toll. She had trouble completing even a simple sentence, and her gait was so unsteady that she was confined permanently to a wheelchair.

There was no disguising that she was in an institution now. Her ward was all tile and linoleum, and she was surrounded by other inmates suffering from advanced neurological disorders, Huntington’s and Parkinson’s, multiple sclerosis, retardation, and dementia. There was one man, younger looking than my mother, who just sat about with his head crooked permanently to one side, his tongue lolling out of his mouth. Another woman, all but immobile, told us how she had been a nurse for many years but was now suffering from Parkinson’s. She seemed to be alert enough and in her right mind.

Which was better? To be past any awareness of your condition—or to be sinking slowly into it, still conscious? I wondered what the point was of trying to extend the longevity of the human body before we knew more about preserving the mind. How much would I understand when I was put in some institution like this? Ellen swore that she would take care of me at home, and I knew she meant it. But I also knew that in the end, she would not be able to do so, that this was my fate I saw here before me.

Visiting my mother was an ordeal to me now. And yet it also felt oddly soothing to just sit with her in silence, while she patted my arm and smiled at me, saying little. It occurred to me that she was tracing the path I would follow. It reminded me of The Vanishing, that creepy European film in which a man is so guilt-stricken over not knowing what became of his lover that he allows her psychotic killer to kill him in the same extended, horrifying manner, just so he can know what she experienced. When my mother first went to live at Landmark, my sister persuaded her to give up her car; her deteriorating physical skills made her a menace to herself and to others on the road. But Pam gave her a few weeks first to get used to the idea, to ease her transition to living on her own, in a strange town, at the age of 75. My mother would usually drive back to Rockport, a place she loved, a place where she had lived for nearly 40 years, and where she no longer belonged. There she would just sit in her car, out on the town wharf, and watch the gulls circling and diving over the harbor. I often thought of her there, and now I understood that I would, one day, know what she was going through.

A Huntington’s drug trial materialized late last year at a Mass General clinic up in Charlestown, Massachusetts—the first interventionary test ever, for at-risk subjects who as yet had displayed no symptoms of the disease. I volunteered immediately. The trial consisted mostly of taking daily supplements of creatine, the bodybuilding drug, which, it was thought, might strengthen and extend the life of neurons. It wouldn’t “cure” the disease, but at my age, preserving as many brain cells as possible—buying time—might prove almost as beneficial.

The first step was another battery of tests, starting with an MRI. When it was over, I got to see a picture of my brain for the first time. Dr. Rosas, who runs the program with Dr. Hersch, her husband, told me that there were no visible signs of Huntington’s yet and pointed out the caudate nuclei, the parts of my brain that were most likely to shrink first. They lay along the edges of the pool of cerebral-spinal fluid that separates the left and right hemispheres of the brain—an area that looks like a pair of dark wings on the MRI, delicate and beautiful. I stared at them for a long time, thinking of how someday the wings would lose their shape as my brain shrunk and they expanded, leaving only more of the blackness.

There was something else on the scan as well. A little white circle, maybe half the size of a dime. Dr. Rosas wanted to know if I’d had any headaches or violent seizures recently. I had not, but it seemed the suspicious little dot could be a tumor in the making. More tests would be required, through my primary-care physician back down in New York. Oh, and it also seemed that I had a cataract in each eye.

I left the clinic in Charlestown before they could diagnose me with malaria or dengue hemorrhagic fever. It took most of a month to get a more detailed cat scan and learn the results. I didn’t really think I had a brain tumor, since I didn’t have any symptoms. I told myself, half-joking, I cannot get two brain diseases in the same year. But I knew enough now not to try to outguess the tests, and the waiting began to drag on me. A few days into the New Year, I went to get those cataracts looked at. They proved to be no real problem, so small now there was nothing to be done but wait for them to grow. Still, coming back from my ophthalmologist’s, I could barely see through my dilated pupils; struggling to dial the number on my cell phone for the MRI results that were due back that same day. Staggering blindly up Riverside Drive, on a blustery January day, the wind whipping at my face and hair, I had to laugh, thinking how my life was turning into a road production of King Lear.

This time, the news was good. I didn’t have a brain tumor. The little white dot was nothing at all. One brain disease to a customer. There was life, there was hope. There was the recognition that all I was going through—the torment of an aging parent, the knowledge that I would likely follow in her footsteps—was really nothing that unusual in our America of aging seniors and genetic testing. What was to be done but to make the most of it?

Back at home, I looked at the scan with my wife. “I’m going to miss that brain,” she said.

“I know,” I told her. “I’m going to miss me, too.”

[roundbox color=”000000″ backgroundcolor=”f5f5f5″ bordercolor=”cc0000″ borderwidth=”2″ borderstyle=”solid” icon=”” ]For medical, psychological, or social service information — contact the Huntington’s Disease Society of America, www.hdsa.org (800) 345-HDSA, info@hdsa.org.HDSA funds research towards treatment and a cure; supports 21 Centers of Excellence at major medical facilities around the U.S., (including one at Columbia, One at North Shore Hospital) that provide medical, psychological and social services, as well as genetic counseling and testing; and provide educational materials for the general public and medical community.

In addition, if anyone would like to donate to the HDSA, a Kevin Baker Research Family Fund has been established. For credit card donations, please call: 212-242-1968 and refer to the Kevin Baker Research Family Fund. To donate by check, please send your contribution to HDSA at 505 8th Ave. Suite 902, New York, NY 10018 Attn: Leah Donnelly.

Anyone giving should request receipt and also inquire about tax deductible status.[/roundbox]

© Copyright New York Magazine