Six games. Seven days.

“How can you stand going to that many games?” Ellen, my very reasonable wife, pointed out. “Don’t you get bored?”

I explained patiently to my wife that it was Major League Baseball’s fault, not mine. From June 26 to July 4, the Yankees would play a remarkable stretch of nine straight games in New York, against both of their fiercest rivals. Mets-Red Sox-Mets, Yankee Stadium and Shea. Three straight, three-game series that promised to rock the city’s baseball world to its core. Six games of dining on franks and beer, and stale Cracker Jack. Six games of catching up with good friends, while we sit like kings in the upper reaches of the upper deck, with the game spread out below us.

“Doesn’t it seem excessive? Even to you?” my wife asked.

Excessive? She had obviously forgotten she was talking to a man who once spent an entire season forming an air bow-and-arrow with his hands whenever Mariano Rivera was about to deliver a pitch to the plate, releasing the imaginary arrow only when the great Rivera let the ball fly. A man who once raced heedlessly through brilliant, October Paris mornings to get to the Place de la Bastille, in order to pick up the International Herald Tribune for the latest update on the 2000 Subway Series. A man who, when a Red Sox-fan friend once flaunted his lucky red shirt in front of him at a playoff game, triumphantly defaced it with a Yankee-blue pen, in order to cancel out its noxious, red mojo.

Six games, seven days. Excessive??

Sunday, June 27. This is the first day, and the biggest test—a day-night doubleheader, two games with a three-hour wait in the Bronx in between.

And yet, the moment I emerge from the D train on the corner of River Avenue and E. 161st Street, I am filled with joy. This is a quintessential urban space, a street corner with a newsstand, half-hidden in the dappled light coming through the elevated rails above…and just across the street is Yankee Stadium. All in all, it doesn’t look much different from when I came to the Stadium with my father, thirty-seven years ago.

I love how firmly the Stadium is ensconced in the city. No ballpark plunked down in a sea of asphalt here. From most of the stands you can see the elevated No. 4 train, and the surrounding tenements and the Bronx County Courthouse seem to loom just over the outfield walls. Inside, the snappy title song from a forgotten, 1960s movie comedy is playing over the public address system—“New York on Sunday/ Big city takin’ a nap”—and in the bright, afternoon sunlight, the vast expanse of green field, and the rows and rows of blue seats almost seem to float beneath me.

The game is a giddy romp for the Yankees, and when it’s over the capacity crowd of over 55,000 fans files more or less happily out (Mets fans being the less). Within minutes, the area around the park reverts to just another, sleepy, New York neighborhood on a Sunday afternoon. Waiting for the second game of my doubleheader, I wander down into Macombs Dam Park, which lies between the Harlem River and the Stadium, and watch a sandlot game there between two teams of young men. Their audience is only a few friends and girlfriends, an idle passerby or two, yet they play with a crackling intensity, sparked by a fiery, Hispanic catcher with carefully braided cornrows that click and sway behind his mask. He barks out constant encouragement and advice to his teammates, taunts and barbs at the opposing batters—dreaming who knows what dreams under the shadows of the legendary stadium.

This was once Bonfire of the Vanities territory. During the 1977 World Series, you could turn on your television and literally see the Bronx burning down, not far beyond the Stadium’s walls—a wrenching urban tragedy that George Steinbrenner, the Yankees’ irascible owner, has tried to exploit ever since, to get a new, taxpayer-funded stadium built for himself, somewhere in Manhattan. But the Bronx has come back, and these days the whole area seems remarkably quiet, and safe. Apparently despairing of Manhattan, Steinbrenner has turned his attention to Macombs Dam and its rough diamonds, already circumscribed by the Yankees’ V.I.P. parking lots. Will the dreaming amateurs there be banished soon to satisfy the Boss’s greed?

But it is dusk now, and time to meet a new set of friends, and go back inside. The nightcap is a much closer contest, like so many ballgames, it comes down to a few, crucial at-bats by both teams in the seventh inning. Baseball is the opera of sports, a game that can seem numblingly dull to the unintiated, only to build suddenly to moments of exquisite tension and beauty. In the seventh inning, my friend Dan, a man who has seen his wife give birth to triplets, is so undone that he holds his Mets’ cap over his face during the critical at-bats.

It doesn’t help. The Mets hit the ball hard, but right at people. The Yanks hit the ball more softly, where there is nobody, and win again. Baseball is not only a game of inches, it is a game of infuriating, mystifying chance. Dan sighs, shakes my hand, and goes home.

So do I—some thirteen hours after I left my apartment. Ellen looks at me, and shakes her head.

“Had enough yet?” she asks.

Oh, no.

June 29. Yankees-Red Sox—the real blood feud, by far the most intense rivalry remaining in American sports. Boston fans pour into the ballpark decked out in full Sox regalia, cheerfully loud and defiant. A rather affected, literary-celebrity cult has formed around the Red Sox in recent decades, all but reveling in the team’s famous fiascoes, just when they seemed on the verge of finally winning it all. But these are the real fans, willing to brave Yankee Stadium, just wanting to see their team finally win a world championship for once in their lives, and the lives of their fathers, and grandfathers.

If Yankee fans are characterized by a demand for excellence that can slip easily into a cranky perfectionism, Sox fans are almost masochistic in their dogged optimism, their need to seize upon even the slightest, momentary advantage. They cheer ecstatically whenever their team takes any lead, holding gleeful little rallies under the el when they win even an early-season game.

It often seems like whistling past the graveyard, this need to laugh in the face of curses and accumulated, New England gloom, but I honor their resilience. I spent most of my childhood in Massachusetts, moving there during the “Impossible Dream” summer of 1967, and I might well have become a Red Sox fan myself, had it not been for the fact that my classmates called my favorite ballplayer in the whole world, “Mickey Mental.”

That insult allowed me to escape decades of Soxian anguish, but I have followed Boston teams for so many years now (albeit it with a gimlet eye) that I feel a certain kinship toward their fans. Some of my best friends are Sox fans (really!) and watching the hordes in red trudge up the steps of the upper deck it occurs to me that New York really has three ball teams again, for the first time since the golden baseball years of the 1950s.

Many of these Sox fans live in the city; not just college students and transplanted New Englanders, but lifelong New Yorkers. Ever since it acquired Pedro Martinez and, especially, Washington Heights’ own Manny Ramirez, the team has become the darling of thousands of Dominican-Americans in the city. A very sweet, young family from Washington Heights sits in the row behind me tonight—all of them, right down to the toddler, dressed head-to-toe in Red Sox road uniforms. It is impossible not to admire this sort of pluck, and I find myself hoping that someday the Red Sox will indeed win the World Series again. Just not in my lifetime.

Tonight, though, the Sox play badly, and the Yankees take full advantage of their every miscue. In the stands, the tension of a good, close game dissolves into brainless insults. At least brawling is not longer commonplace at Yankees-Sox games as it was back in the 1970s, the last time the rivalry between the two teams reached fever pitch, but New York (and Boston) fans badly need to get some better chants.

All week long, it is the same: The Yankees suck. The Mets suck. The Red Sox suck. Boston sucks. The closest thing to wit is the Yankee fans’ taunt of “19-18!” referring to the last time the Red Sox won the World Series, and it is hoary enough to have probably started sometime in 1919.

Then, without any warning, the face of Vice President Dick Cheney, watching the game from a box seat, is suddenly flashed upon the scoreboard. Immediately, the entire Stadium erupts in raucous booing. Cheney’s image flicks off so quickly it might have been a mirage. For a brief moment, politics has brought us together again, Yankee and Red Sox fans alike, in blue-state solidarity. Who says the Bush administration isn’t uniting us?

July 1. This is the best game of the week, maybe one of the best single, regular-season games ever played. This is one of the great attributes of baseball, the game that is played everyday. Almost no one remembers regular-season hockey, or basketball, or even football games anymore. But in baseball, astonishing things can happen anytime—plays and moments that even the most devoted fan has never witnessed before, and which he will remember for the rest of his life.

The Yankees take a surprising early lead, even though they are starting a raw, young rookie against Martinez, the Red Sox ace. The Sox battle back to tie it, and the game goes into extra innings. Again and again, both teams load the bases or put men in scoring position, only to be thwarted by improbable, impossible plays. The Red Sox resort repeatedly to incredible strategic shifts, bringing one of their outfielders into the infield—the players tossing the proper gloves back and forth to each other, a blizzard of leather flying through the night air; making this epic, major-league battle seem instantly like a boys’ pick-up game again. The Yankees’ Derek Jeter makes a play that is instantly added to his already considerable legend, robbing Boston’s Trot Nixon of a potential, game-winning hit after a long run—the momentum sending him hurtling into the box seats, and cutting his face open.

For all the griping about how much money ballplayers make today—and they do make an obscene amount—where else in America can you see millionaires risking serious physical injury out of pride, out of the desire to do something, make some play that no one has ever seen before? Long ago, in the considerably less-well-paid, gritty days of baseball, when ballplayers badly needed their jobs, there was a beautiful centerfielder for the Brooklyn Dodgers named Pete Reiser, whose career was tragically shortened by his tendency to run into outfield walls after flyballs. Now, some sixty years later, here is Jeter, with considerably less motivation, playing just as recklessly.

I can’t say it’s a good thing, for anyone to risk serious injury trying to catch a baseball—but I can certainly understand the Yankee fans who have greeted Jeter with standing ovations ever since; why whole families appear at the Stadium now, wearing matching chin bandages in tribute. Jeter’s heedlessness matches the fan’s own irrationality, our love of the game that transcends the exorbitant prices we pay to watch, or the indifferent way we are treated by the Lords of Baseball in their parks. It is a quality that seems to me to be steadily disappearing in America—the love of something for itself, instead of what profit it can afford you.

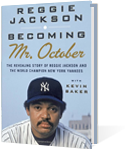

Appropriately, I am at the game this night with Chris, one of my oldest and closest friends in the world. We met over twenty-five years ago, on another, gaudy, improbable day at Yankee Stadium, the “Reggie Bar” game. Responding to Reggie Jackson’s boast that if he played in New York they would name a candy bar after him, some confectioner did just that. Samples of the bar were given away at the Yankees’ home opener in 1978, and when Reggie responded with a mighty home run, the bars were tossed spontaneously onto the field. Thousands of little, orange-and-blue squares, fluttering slowly down from the stands—the kind of tribute that might greet a bullfighter.

A few years later, sharing my first apartment with Chris and his fianceé, Ann, we came home to find the place looted, always a jolting, violative experience. The only thing left was a secondhand, black-and-white TV with a broken antenna, which even the junkies doubtless found beneath them. That night, the three of us consoled ourselves by sitting on a bed in our desolate home, watching a fuzzy Yankee broadcast and all clutching onto the severed antenna, trying to will Reggie to hit another home run through it.

Now Chris is a high-school classics teacher in Queens, and he has brought his two, wonderful sons to the game, one of them already a teenager. Still, he deliberately retains his old fanaticism, beyond what even I am capable of.

“Beware of losing the thing you love,” he warned me once, when I suggested we should take these games less seriously. During a close game this otherwise mature, responsible teacher of children seethes, laughs, mocks, and rants. Tonight, as the game continues through one, excruciating extra-inning after another, his face begins to resemble that of the psychotic defense worker Michael Douglas played in Falling Down. When it looks—erroneously—as if the umpires have blown a call on a marvelous play by Alex Rodriguez, he tosses his scorecard down the grandstand in disgust.

By the thirteenth inning, the Yankees have run through their pitchers, and are down to a journeyman hurler named Tanyon Sturtze (whom we fans prefer to call Keyser Soze). The Red Sox fans predictably go wild, assured of victory. Chris can take no more, and actually has to leave the game, the flip side of such an all-consuming passion.

It may be just as well. Manny Ramirez promptly belts a long home run off Sturtze, and I fear that Chris might well have leaped from the stands in suicidal protest against the whims of the gods. I decide to stay on, knowing that sooner or later the gods always turn against the Sox. Sure enough, in the bottom of the thirteenth, one strike away from losing, the Yankees stage yet another comeback, winning the game on a hit by their back-up catcher. The Sox fans look staggered, stunned by one more, incredible loss. But by the time we hit the subways everyone seems to be glowing, exhausted, amazed, excited by what we have been privileged to see, just because we happened to go to a ballgame this night.

July 2 & 3. Shea Stadium. This is where the future went to die.

Shea is another Robert Moses excrescence, the product of his long obsession with building a monument to himself in Flushing Meadows. It was rushed into completion for the opening of the 1964 World’s Fair, and it reflects the same, pixilated, ’60s idea of what the twenty-first century was supposed to look like. That is, mostly shabby building materials in garish colors. Shea was built by a man who neither knew nor cared anything for baseball, and it shows; there are not even any real bleachers in the place.

It was also meant to cater to that other wave of the future, the suburbs. Shea’s location seems to have been perfectly calculated to be as far as possible from every single neighborhood in the city other than Flushing. For most of us coming from Manhattan, it means a nearly endless ride along the No. 7 line.

To be fair, neither major-league park in New York provides anything close to a fan-friendly experience. Both Yankee and Shea Stadium are generally filthy and sloppily maintained, and the prices for everything are extortionate. The public address systems—especially at Yankee Stadium—bombard one relentlessly with ads and bad pop music between innings, usually at decibel-levels so extreme you literally have to shout in order to converse with the person in the seat next to you.

But at Shea Stadium I feared not only for my hearing but for my life. Just before the Friday night game against the Yankees, there was an intense, five-minute cloudburst, which then cleared immediately. Nonetheless, for the entire rest of the game, water dripped down on my friends and I in our seats. This was particularly disturbing because we were seated in the mezzanine, underneath the upper deck—and the water seemed to be coming directly through an open sieve in the concrete, located next to one of the supporting, steel beams.

When we went to tell an extremely nice, harried young woman who was handling customer complaints, there were at least a dozen other fans there with the same problem. The nice young lady told us there were no other seats available, and promised us all tickets to future games, but I thought this was somewhat beside the point.

Were we all about to die? Shouldn’t someone alert Fred Wilpon, the Mets’ owner and a major real estate developer, who might be expected to know something about fatal structural damage?

The game on the field, though, was a revelation, as a young Mets team which had been struggling all season, sprung suddenly to life. They gleefully pummeled the overdog Yankees on this night…as my friends and I alternated between staring wistfully down at rows of empty, dry, corporate-owned box seats below, and anxiously up at the ceaseless drip of water coming through the concrete above, wondering if we were about to be crushed. The next afternoon they beat the Yankees again, turning the tables on them in yet another thrilling, seesaw battle that is decided in the bottom of the ninth when Keyser…er, Tanyon Sturtze flips the ball over the catcher’s head.

I limp out of the stadium, done at last, wondering how many hot dogs it takes to contract sodium poisoning. Despite all the thrills of the past week, I am still nettled to lose, to lose anything. A Mets fan smirks by the escalator, “Goodbye, Yankee! Thanks for coming!” I tell him, “See you in October. Oh, that’s right, I won’t.” (Snappy comeback, eh?)

But in fact the Mets seem to have turned their season around, and are currently about as well-situated to make the World Series as the Yankees are. So are the Red Sox, who regrouped once again up in Fenway Park, and seem as grimly determined as ever to keep all of New England up well into the October nights to come.

It is I who am exhausted. Watching me crawl back home after the last, draining, game, my wife asks knowingly, “Had enough? No more games until September, right?”

Well, maybe. But whenever I go out to the ballpark again very soon, the games are always there, filling up the little spaces in our lives. I will listen to them on my walkman while I stumble around the reservoir running track in Central Park, cursing and fuming under my breath. Restlessly flicking on the television to check the score every evening, before I return to my writing desk. Excitedly jabbering over the phone to my friends and fellow fanatics, “Did you see that?” Even in the winter, we will scheme for the summer to come and reminisce over seasons and games past.

Baseball is one of those useful, useless obsessions, indispensable in the modern world. It is, simply, a beautiful diversion, into which we fans pour our free-floating anxieties, dreams, and frustrations.

Six games in seven days? It’s not nearly enough.