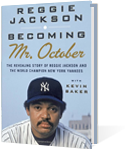

Before the Storm

Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus

By Rick Pearlstein

Hill and Wang, 2001

671 pages

BOOK REVIEW

In January of 1964, the Barry Goldwater campaign rolled into the rockribbed, conservative state of New Hampshire, ready to do battle for the Lord and the Republican nomination for president. The Goldwaterites were supremely confident, and why not? At that moment they were the best-organized, most ruthless political force in the country. Bolstered by oceans of cash and thousands of volunteers, they had been planning and training for this moment for nearly three years. The only thing that stood in their way was New York’s liberal governor, Nelson Rockefeller—and his campaign had been hemorrhaging steadily since the spring before, when he had divorced his wife of many years to wed another divorcee.

After weeks of filling halls with cheering crowds, the Goldwaterites tramped confidently to the polls on March 10 and, in a record turnout…drew 23 percent of the vote. They finished 12 points behind a write-in campaign run on behalf of Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr.—then serving as ambassador in Saigon—by four self-appointed gadflies, with virtually no money. Senator Goldwater barely finished ahead of Rockefeller—or another write-in campaign organized on behalf of Richard Nixon.

Goldwater continued to underwhelm in almost every primary he entered. He lost a crucial showdown to Rockefeller in Oregon by nearly 2-1, finishing a distant third behind Lodge. Only by squeaking out a victory in California—after Happy Rockefeller gave birth to the new couple’s first child the day before the primary—was Goldwater spared from losing every important test he faced at the polls.

And yet, at the Republican convention in San Francisco that July, while thousands of his admirers shook the rafters of the Cow Palace, Goldwater breezed to the nomination on the first ballot.

Just how such a thing could have come to pass is at the heart of Rick Perlstein’s new history, Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus. It is, as well, the paradox that undoes his book at every turn.

For Perlstein, the real political story of the 1960s was the rise of the right-wing. Goldwater’s nomination marked the movement’s coming of age, a victory that would forever rend what Perlstein characterizes as a smug, hubristic, and ultimately dangerous, liberal consensus.

“After the off-year elections a mere two years later [1966], conservatives so dominated Congress that Lyndon Johnson couldn’t get up a majority to appropriate money for rodent control in the slums,” Perlstein writes.

It barely mattered that Goldwater had failed to impress in the primaries—or that he would go down to a crushing defeat in November. The triumphs of Nixon, Reagan, Bush one and Bush two; Gingrich, Scalia, Clinton(s) and the Democratic Leadership Council would follow inexorably.

In Perlstein’s assessment, “Here is one time, at least, in which history was written by the losers.”

Before the Storm is an attempt to trace just who these “losers” were, and how they finally won—to chart all the myriad tributaries of thought and action that must feed into the main current of any successful, American political movement. It is a worthy endeavor, the sort of thing that has been done repeatedly for the great liberal-left movements, in such outstanding works as Lawrence Goodwyn’s The Populist Moment; Arthur Schlesinger, Jr.’s The Age of > Roosevelt, Irving Bernstein’s A History of the American Worker; Richard Kluger’s Simple Justice; and Taylor Branch’s superb, ongoing account of Martin Luther King and the civil rights movement.

Before the Storm is every bit as ambitious. Perlstein has done copious research, which is shown to its best affect in the early chapters, as he traces the evolution of right-wing ideology since World War II. He bends over backwards to be fair in these segments. And yet—one is struck by nothing so much as how utterly dismal modern, conservative thought has been. How meager and self-serving it all seems; how redolent of racist and quasi-fascist fantasies!

Here is the old gallery of grotesques: Robert Welch, the candy magnate who founded the John Birch Society—and who was known ever after to its adherents as “The Founder”—giving his two-day lectures on how the Eisenhower administration was a communist plot. Phyllis Schlafly, the Harvard-educated Ph.D., leaving home on her never-ending junket to insist that women stay in the home. William Buckley, Jr., blithely using daddy’s money to champion rugged individualism.

Here are all the endless conspiracy theories and the teeny-tiny revelations; the obsessions with taxes and government regulations and the United Nations; the anti-fluoridation campaigns and the nuclear wet dreams. Ronald Reagan, seeing the light in his umpteenth, pre-packaged stump speech for General Electric. Gen. Curtis LeMay—then the Air Force chief of staff—urging his pre-emptive nuclear strikes againt the Russians, the Chinese, the Cubans. George Wallace, swearing like a latter-day Scarlett O’Hara, “I will nevah be out-nigguhed again!”

It is a masterful overview—and yet, it raises immediate suspicions. How could such thin soil have produced a truly mass, democratic movement?

By 1960, conservative hopes had come to center on Goldwater, a bluff, likable senator from Arizona, endowed with rugged good looks and a small personal fortune from an inherited department store. He had also barely completed a year of college and was widely thought to lack the intellectual breadth necessary to be an American president in the twentieth century.

This was a sentiment that Goldwater himself was modest enough to share—and besides, most conservatives doubted that they could really get one of their own nominated, anyway. Time and again, conservatives from “the heartland” had marched off to a national convention, believing they had the votes to nominate their great champion, Robert Taft. Yet somehow, an Eastern, Wall Street cabal had always applied enough money or enough influence to supplant Taft with more moderate candidates like Eisenhower, or Thomas Dewey, or Wendell Willkie.

Enter Clifton White. White was a longtime Republican activist, the forefather of all the campaign gurus who currently despoil our political landscape—and like all great political gurus, he possessed the hedgehog’s knowledge of one, big thing. White understood that a temporary power vacuum had opened up in the American party system. The old machines and kingmakers were in decline, while the universal primary system was not yet in place.

If you could flood enough precinct caucuses with true believers—both well-trained in parliamentary procedure and willing to shout down any dissenters—you could elect enough delegates to control the district caucuses. Control enough district caucuses and you had the state delegation, and so on to San Francisco.

Beginning in1961—and working largely in secrecy, so as not to alert the fading cabal—White did just that, building the far right’s first, national political apparatus. The race was all over before it began. To their dismay, the other leading candidates discovered that it didn’t matter how many primaries they won, or how good they looked in the polls. Goldwater’s men controlled the state caucuses, where the vast majority of delegates were still selected.

All this makes for a fascinating story of political trench warfare—albeit one told before, by Teddy White, in The Making of the President, 1964, and in Clif White’s own campaign memoirs—and Perlstein becomes engrossed in it. And yet, it is not the story of a mass democratic movement, so much as something akin to a coup.

As Perlstein himself admits, once the television lights flipped on and America got a good look at what Clif White had wrought, it was horrified. The convention was a zoo, stuffed with John Birchers, Minutemen, Young Americans for Freedom, the whole rest of the right-wing menagerie. They occupied themselves physically chasing newsmen and party dissenters from the hall, and shouting down Rockefeller—before a prime time audience—when he tried to submit a party plank condemning “extremism” of all kinds.

By the time it was all over, polls showed that Goldwater had the support of less than one-fifth of the nation’s voters, and many GOP candidates spent the election season running as far from the national ticket as they could get. In November, the great, right-wing hope lost the popular vote to Lyndon Johnson by 61-38 percent, and Republicans everywhere suffered devastating losses. By the end of 1964, some 53 percent of Americans polled considered themselves Democrats, as opposed to only 25 percent who identified with Republicans.

Why, then, should Barry Goldwater not be considered, say, the George McGovern of the Republican party? Perlstein offers up several technical explanations that soon test both our credulity and our common sense. The debacle in the New Hampshire primary, for instance, is attributed to the untimely release of Stanley Kubrick’s wicked nuclear-war satire, Dr. Strangelove. Goldwater, you see, had just voiced his belief that battlefield nuclear weapons could be entrusted to area commanders—and that they should be used to “defoliate” the Ho Chi Minh trail in Vietnam.

“Attentive viewers couldn’t fail to understand that Kubrick was satirizing an entire system, not any of the system’s cogs,” Perlstein is helpful enough to explain.

“But most viewers were not attentive. Americans prefer to isolate villains who despoil a preexisting innocence, rather than admit that there might not have been any innocence there in the first place.”

Ah, those inattentive Americans, unable to understand Dr. Strangelove! This sort of condescension pervades Perlstein’s analysis. Elsewhere, a crowd in Detroit’s Cadillac Square is described as “sturdy proletarians,” while viewers of a Goldwater holiday telecast are described as “the folks watching at home, lazy, fat, and overcontent from too much Memorial Day bratwurst and beer…”

Perlstein suggests that all the sturdy proles might still have been won over, had Goldwater not shunted Clif White aside for the general election. He presents no real evidence for this; objectively, getting 38 percent of the vote when your candidate is garnering less than 20 percent after his own convention might be considered some feat.

But you see, White had plans to exploit Americans’ lowest fears through a lurid film that featured clips of pornography, and rioting urban blacks. (Apparently, movie-goers attention spans had improved between March and November.) And surely, he implies, White would have better exploited the arrest of one of Johnson’s aides for making a pass at another man in a Washington, D.C., restroom.

Well, we can all be sorry we missed out on that campaign, but it still does not quite a mass political movement make. In fact, the voices of almost any conservatives foot soldiers soon become conspicuous in their absence. In a typical passage, Perlstein writes that true believers at the San Francisco “would have been altogether disgusted by the goings-on at the Haight” or “might have been amused” and that “some might have taken in the country’s first topless dancing act.” But we never do quite hear what they did or didn’t (even though we are assured, “it was their Woodstock.”), and the lack of such direct accounts helps to reinforce the impression that the Goldwater campaign, like so much else of the conservative movement, was an affair run first and foremost from the top down.

Nor does it help that Perlstein resorts to one shoddy distortion after another to hold this impression at bay. Thus we are told that by 1961, three years after its inception, the John Birch Society “had 20,000 members…or 60,000, or 100,000″—yet we never learn that the organization was moribund before the end of the decade, or that the average American was about as likely to know a member of the Nation of Islam as a Bircher. We are eagerly informed that Young Americans for Freedom (YAF), the right-wing youth movement founded on William Buckley’s estate, “won 5,400 new recruits in the summer of 1964, compared to [the left-wing] SDS’s total membership of 1,500″—but Perlstein doesn’t mention that within another four years Students for a Democratic Society had thousands of members at campuses all over the country, while the YAF had devolved into the curious little cult of personality it remains to this day.

Again and again, we are told some hot new, right-wing book is “a bestseller,” or “was flying off the shelves by the tens of thousands,” or “had sold enough copies to supply one out of every ten men, women, and children in the country”—only to have Perlstein admit, a few pages or a few paragraphs later, that “There always was another Birchite millionaire willing to spring for a lot of a few thousand more [books] to sprinkle around like so many Gideon Bibles.” Again and again, he feels the need to impress us with how many millionaires it took to fuel this supposedly mass, democratic movement, from Buckley, to Henry Regnery, to H.L. Hunt, to a young Richard Mellon Scaife (oh, was Richard Mellon Scaife every truly young?)

Like the hellish legions Macbeth’s weird sisters would summon, Perlstein’s right-wing masses somehow never quite manage to materialize. Rather than demonstrate how Goldwater’s catastrophic defeat created new Republican voters, Perlstein simply . dangles certain politicans near the end of Before the Storm, like a self-evident Q.E.D. There is George Wallace—much more the real father of the modern American right than Barry Goldwater ever was. Yet even Wallace, running for president under optimum conditions in 1968, when it seemed as if America were coming apart at the seams, was able to garner only 13 percent of the popular vote, and did not carry a state outside of the Deep South. Richard Nixon, who did win in 1968, was forced to spend much of his term expanding the social welfare state, creating the Environmental Protection Agency, and submitting an idea for a guaranteed national income to Congress.

Then there is Reagan. Perlstein makes much of Ronnie’s political coming out in 1964, including a speech in the closing days of the campaign, broadcast over national television. The speech is often referred to in conservative circles—as “The Speech”—yet it is almost never quoted. It is stuffed full of Reagan’s usual, amiable lies and tall tales, but the bigger problem seems to be that it is also full of proposals the right was not keen to bring up again after Goldwater’s campaign, such as getting rid of Social Security, the Tennessee Valley Authority, and even some veterans’ benefits. Yes, Reagan was able to win election as governor of California in 1966—where he rarely dared to assault his state’s extensive social welfare state with anything more than words. Trying to run for president as a fire-breathing conservative again in 1976, he could not oust an unelected, moderate Republican incumbent who had become a national laughingstock. In 1980, Reagan still claimed less than 52 percent of the popular vote against Jimmy Carter, and the evidence strongly suggests that he was one rescue helicopter engine away from becoming a genial footnote to history. And once in office, as George Will characterized it, President Reagan’s conservatism consisted of little more than conserving the essentials of the New Deal.

Even in their greatest moments of triumph, conservative politicians have rarely been emboldened to enact much of the right-wing agenda. This is in part because that agenda is based upon the airiest of fantasies, but mostly because conservative movements have simply never drawn the sort of sustained, mass participation that marked the civil rights, environmental, women’s, gay rights, labor, or anti-nuclear movements. The closest they have come is the anti-abortion movement, and even here, after a few mass demonstrations, their numbers melted away without making a dent in Americans’ support for legal abortion. Instead, their work was largely done for them by a small handful of the faithful, whose campaign of terror, assassinating physicians and firebombing clinics, has effectively expunged a woman’s right to choose in most parts of the country.

This is hardly surprising, since the American right has, in fact, battened on nearly every anti-democratic development of the past four decades, from “white backlash” and the illegal, undeclared war in Vietnam, right through to the theft of the 2000 presidential election by way of mob violence, racial manipulation of the voting rolls, and a partisan judiciary. Unable to sustain a mass base, the right has had to rely on all that limits mass participation, on everything that divides, alienates, and disqualifies voters—on the constant denigration of government itself, as a somehow illegitimate entity, a malevolent intrusion into people’s lives.

It’s little wonder, then, that Perlstein constantly refers to rightist “cadres”—or that Clif White actively modeled his Goldwater campaign after Communist archetypes of organization and strategy. Perlstein even tries to confer some sort of bizarre validation upon the right, by noting how many former Communists became ardent conservatives, or how comfortable young conservatives were “joining members of the Young People’s Socialist League in rousing choruses of radical songs.” But why not? Both sides put a premium on tactics such as “burrowing from within,” massive propaganda that adheres to a strict party line, and the promotion of anything that creates contempt for the prevailing order. Both share a fundamentally infantile, messianic world view, and reserve their greatest contempt for liberalism—as does the author.

Perlstein writes of the “liberal consensus” the way undergraduates in the 1960s spoke knowingly of “the Establishment,” or that undergraduates of the 1990s spoke of The Matrix. Alternately referred to as “The Story,” the consensus is an oppressive, homogenizing monolith, made up of the government, the military, big business, labor, and the media.

The consensus is, by its very definition, to be held reponsible for everything, even the crudest fantasies of its opponents, such as a fleeting rumor that ” “African Negro troops, who are cannibals”[sic]—were secretly rehearsing in the Georgia swamps under the command of a Russian colonel for a UN martial-law takeover of the United States.” “In America citizens are charged with making their own sense of the world around them. But they were refused the information to do so by Cold War secrecy. So they did what they could with the facts available. Secret armies trained in out-of-the-way forests did try to take over countries; we had tried it with the Bay of Pigs,” explains Perlstein, back in full Mr. Rogers mode.

He wraps himself into many such contortions, and worse, in trying to prove the full iniquity of “The Story.” A reader of Before the Storm might well conclude, for instance, that unemployment was rampant in America in the 1960s—when in fact it was barely extant—or, thanks to Perlstein’s combing of back page fillers and tabloid headlines, that the nation was a raging cauldron of random violence, psychosis, and discontent.

Much more disturbing, though, is the odious moral neutralism that Perlstein affects, in order to debunk the consensus Often, his own rhetoric is indistinguishable from that to be found in The National Review. In the world of Rick Perlstein, no conservative has ever lost a debate on any subject, few are ever less than brilliant and charming, and almost none ever make anything less than a scintillating speech that instantly brings hordes of those sturdy proles (“S.P.’s”?) to their side. Meanwhile, the word “liberal” is almost never used without the modifier “smug” in front of it; they constantly “sputter,” “simpered” and are “patronizing”—and possibly even certifiable. “In a clinical sense, Johnson’s paranoia and bipolar tendencies bespoke far worse mental health,” Dr. Perlstein informs us, referring to two mental breakdowns Goldwater had suffered in the 1930s.

The more racist and militarist sentiments of right-wing leaders are constantly downplayed—while leading liberals are pilloried for lesser offenses. Perlstein insists, for example, that Goldwater’s infamous tag line from his acceptance speech in San Francisco—”I would remind you that extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice! And let me remind you also—that moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue!”—”hardly differed in tone from President Kennedy’s vaunted inaugural address: ‘We shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, to assure the survival and the success of liberty.”

Nonsense. Liberty and justice are by their very definition anathema to “extremism”; they are impossible without “sacrifice.” Yet Perlstein is determined to legitimize the right. He refers repeatedly to a woman with a Goldwater button who “became the Rosa Parks of the San Francisco streetcars when she flamboyantly defied the unwritten rule against women standing on the running boards and caused such a disturbance that she ended up getting arrested”—a repugnant comparison, and one that only demonstrates that Perlstein has not the least understanding of what either Parks or the civil rights movement was all about.

Elsewhere, he writes of how “More and more Americans, in fact, were beginning to look at politics as Martin Luther King did—and as Barry Goldwater, Michael Harrington, Rachel Carson, James Baldwin, and Betty Friedan did—as a theater of morality, of absolutes.” Rubbish. Except for Goldwater, none of the above individuals celebrated “absolutes.” If anything, they stood squarely in the middle of the liberal, reformist tradition, fighting for such highly practical things as guaranteeing full citizenship for women and African-Americans, reducing poverty, and banning DDT.

Increasingly, one has the feeling that Perlstein really does not have a good grip on the era at all—and not least in his insistence on the whole idea of “the liberal consensus” in the first place.

For proof, Perlstein offers mostly clips from period editorials and columnists, and the stump speeches of politicians. This is the historical equivalent of proving the existence of the yeti by paying Tibetan peasants to show you its droppings. Insisting on the unity of the American people is a wish that politicians and editorial writers like to throw up into the ozone periodically, and you could as easily collect like quotes from any era in American history.

There was indeed a general, liberal ascendancy from 1932-1980 or so, but it was never uncontested or all-powerful—never a consensus. Throughout this period, liberalism was under constant assault—from plutocrats pouring money into anti-union drives and conservative campaign coffers; from reactionary Southern and Republican congressmen blocking most progressive and civil rights legislation; from red-baiters and professional moralizers—from the three-quarters of the nation’s newspapers that backed the more conservative candidate in nearly every presidential election.

In short, very much the same political landscape that Perlstein describes. Key parts of the consensus keep coming off under his pen like, well, like petals on a daisy. The conservative movement rose for years on the cash of one corporate millionaire after another (so much for the business end of the consensus), generals urged nuclear war (there goes the military), and we hear of “Barry Goldwater’s nine-year string of good press” and syndicated newspaper column (so much for the press.)

Or, perhaps the real problem is not Perlstein’s grasp of the era, but the fact that he possesses only the faintest notion of how a democracy actually works.

“In their conclusions the White House betrayed a constellation of unspoken assumptions about race relations—about social relations—in the United States: introduce bold legislation and the troublemakers would quit, like kidnappers who had been paid their ransom,” he writes, describing the Kennedy’s administration’s proposal of what would become the Civil Rights Act, in the wake of the Birmingham movement.

“Theirs was an almost desperate belief that America was by definition a placid place, if only ‘extremists’ could be kept in check. That didn’t just mean the racists who perpetrated the violence—but also those who ‘disturbed the peace’ on the other side by protesting racism.”

But it is really Perlstein who is being naïve here. This is the mechanics of democracies and their leaders—we push them, and they pull us. It’s highly unlikely that the sons of Joe Kennedy ever thought of America as “a placid place,” but they were certainly trying to use legal measures and moral suasion to give black Americans what they wanted. Of course they were trying to promote harmony and prosperity. What else should they have done? Passed out arms? Ignored the whole mess?

“Labor and management, allies not adversaries, reasoning together for their common good: this was Lyndon Johnson’s dream,” Perlstein scoffs at another point. Well, gosh, Rick—isn’t that the American dream?

Perlstein rightly lambasts the Kennedy and Johnson administrations for their foot-dragging on civil rights, and for the excesses of the Cold War—particularly our blind stumble into Vietnam. But the worst of these transgressions always came about when both presidents departed from liberal principles—just as democracy has receded over the past thirty years whenever liberals acceded to right-wing demands and mythologies.

The great story of the 1960s is what liberalism accomplished. America became the first major state in modern history to guarantee the full citizenship of a sizable, racial minority. And its civilian leaders successfully resisted the repeated, urgent appeals of its military chiefs to launch a “pre-emptive” war of mass destruction.

If you don’t think that’s so much, consider what a Goldwater administration might have been like—with its intimate ties to racist Southern whites; its support for using nukes in Vietnam and invading Cuba; its stated determination to resume aboveground nuclear testing—and not least, its adoration of those same, trigger-happy generals. (Goldwater in 1963, before something called the “Military Order of the World Wars”: “I say fear the civilians. They’re taking over.”)

Perlstein has turned history on its head—but not as he thinks. “The consensus” and “The Story” are what hold sway now—not what did in the 1960s. That America was a place where a generation of liberal victories had produced a nation open and secure enough to throw up a Barry Goldwater—and to soundly repudiate him. The apogee of the liberal epoch marked a brilliant flowering of cultural and political diversity, where all sorts of views were entertained and debated, however raucously. Turn on your television set in the 1960s—even with a mere three channels—and you might see anyone from Malcolm X to the head of the Ku Klux Klan, or the American Nazi party; from Michael Harrington to Milton Friedman.

Quite a contrast to the imposed culture we have today, where we are granted ever more channels, and ever fewer choices. Perlstein, who is a contributor to The Nation, has made it clear that he would like to use Before the Storm as a rallying cry for the left—that the triumph of the conservatives after Goldwater would be no different from the Democrats being able, in just a few short years, to routinely elect leaders “whose positions included halving the military budget, socializing the medical system, reregulating the communications and electrical industries, establishing a guaranteed minimum income for all Americans, and equalizing funding for all schools regardless of property valuations—and who promised to fire Alan Greenspan, counseled withdrawal from the World Trade Organization, and, for good measure, spoke warmly of adolescent sexual experimentations.”

What he doesn’t seem to understand is that majorities of Americans support many of those positions now, at least according to opinion polls. It doesn’t matter. For the triumph of the right has not been the triumph of some mass, democratic movement but the triumph of Clif White—elite, privately financed cadres, able to adroitly discourage or ignore what most people think.

There is no figure in Before the Storm—no segregationist, no missile-rattler—who draws the approbation of Perlstein so consistently as Lyndon Johnson, the rough beast of democracy himself. No doubt his corrupt, old hide deserves most of this tanning—and yet, in the context of our present politics, he comes off as an almost beguiling figure. He was a man who had no illusions about the rough-and-tumble of politics, one who had lived on the most unsavory sides of democracy—and yet could still summon up an inspiring vision of what America could be.

It may be that, by 1966, Johnson could not get a rodent control bill passed, but that is only another one of Perlstein’s distortions. Even as a widely hated, lame-duck in 1968, he was able to get the Fair Housing Act into law—a piece of crucial civil rights legislation that has saved us untold strife and litigation ever since. Like so much else of the Great Society agenda that Perlstein finds hubristic, it was an eminently practical and successful answer to a pressing social problem.

Yet Johnson’s best moment was undoubtedly one evening during the 1964 campaign that Perlstein recounts. Despite a storm of insults and death threats, directed at both himself and his wife, Johnson insisted on traveling to the heart of the white South, and bearding his countrymen in their den.

“All these years they have kept their foot on our necks by appealing to our animosities and dividing us,” he said, informing a hostile New Orleans audience to its face that he would enforce the new civil rights laws. “My poor old state, they haven’t heard a Democratic speech in thirty years. All they ever hear at election time is, ‘Nigger! Nigger! Nigger!’”

Perlstein treats this with his usual, patronizing contempt—”He wanted a mandate”—but it is impossible to conceive of any American politician today capable of such courage or candor. Reading it again I was reminded of that sad, sordid incident in the District of Columbia a few years ago, when a covey of city officials wanted to fire a financial officer for describing the city’s social services budget as “niggardly.” And yet, not a one of them managed to object to its actual niggardliness. They would cavil at a word, but swallow the deed whole. Such is life under our illiberal consensus.

© Copyright Harper’s Magazine 2002