Mayor Bloomberg’s new campaign to crack down on violations of the city’s excessive noise ordinances will no doubt be met with almost universal acclaim. It is, after all, the rare New Yorker who has not been driven nearly to homicide by one completely unnecessary, inconsiderate, and brain-rattling noise or another, usually in the middle of the night. In my neighborhood, the major culprits include semi-trailers blasting their air horns as they hurtle up Amsterdam Avenue, apparently trying to break the sound barrier (Note to the nation’s truckers: New York is not a movie set. People actually live here.), or that first, dreaded blast of music that heralds what my wife and I have come to call, “Three A.M. Salsa Party” (pre-empted occasionally by “Two A.M. Hip-Hop Jam” or “Four A.M. Cruisin’ to the Oldies”).

Believe it or not, though, New York is actually a much more quiet city than it was, say, a hundred years ago. Try to imagine tens of thousands of iron-rimmed wagon wheels rattling over cobblestone streets, or a steam engine on that elevated rail just outside the window.

And what about those noises that we love? They do exist, although I imagine that our taste in sound is as subjective as everything else in the city.

One rule of thumb, I suspect, is that distance lends enchantment when it comes to city noises. Much as I loathe the truck grand prix a few yards from my door, I am always transported by the distant wail of truck brakes, somewhere out in the night. There is something achingly, primordially lonely about that sound. Then there is the faint twang of the subway rails as a train starts to approach the station, still several blocks away. It is a small sound, but the very embodiment of anticipation—much better than the actual, clamorous arrival of the Broadway Local.

Even better is the rumble of the Metro North trains as they emerge from under Park Avenue, which we can hear clear across town sometimes on particularly still nights. This is an atavistic, rural noise, one that feels as if it should have been banished from the city long ago—much like the bells of the beautiful, Romanesque church of St. Michael’s, sounding every half-hour, just across the street from my apartment building.

I feel privileged to be able to hear such sounds still. They make one cognizant of another urban noise that has vanished, although up to a generation ago it was nearly ubiquitous. That is the human voice of the street vendor, hawking his wares. No doubt, New Yorkers of a certain age can still remember the used-clothes collector, singing out his mournful cry, “I cash clothes!” as he shambled from neighborhood to neighborhood, laden down with used dresses, suits, hats. Not to mention the cries of all the newsies, pushcart peddlers, knife sharpeners; or the fish, greens, sweet-potato, ice, and even coal sellers of Harlem, who specialized in setting their own, sly lyrics to the popular tunes of the 1930s and ’40s (“A tisket, a tasket/ I sell fish by thebasket/ And if you folks don’t buy some fish/ I’m gonna put you in a casket…”).

The songs of the peddlers must have all but defined the tempo of our city throughout most of its history. Even more so in the nineteenth century, when street vendors were everywhere, aggressively peddling oysters, lemonade, cabbages, matches, handy black funeral veils, or pears in syrup served in little clay dishes. Then there were the hot corn girls, pre-Civil War New York’s twisted, virgin-whore fantasy. These were teenage girls, always barefoot, wearing trademark, calico shawls, and selling ears of fresh-roasted corn—and sometimes themselves. They sang plucky little verses at the passing men who pitied them, and wanted to protect them—or to buy them:

“Hot corn! Hot corn!

Here’s your lily-white corn!

All you that’s got money—

Poor me that’s got none—

Come buy my lily-hot corn

And let me go home!”

As sad and sordid as the existence of the hot corn girls was, their cries could evoke the sort of instant nostalgia that is one of the greatest rewards of living in a large city. Even so strait-laced a puritan as George Templeton Strong wrote in his diaries “of sultry nights in August or early September when one has walked through close, unfragrant air and flooding moonlight and crowds, in Broadway or the Bowery, and heard the cry [of the hot-corn girls] rising at every corner, or has been lulled to sleep by its mournful cadence in the distance as he lay under only a sheet and wondered if tomorrow would be cooler. Alas for some far-off times when I remember so to have heard it!”

It is these human noises that ultimately convey the romance of city life. What New Yorker doesn’t understand the essentially urban experience inherent in, say, the lyrics of that sublime, Holt Marvel-Jack Strachey-Harry Link standard, These Foolish Things:

“A tinkling piano in the next apartment,

Those stumbling words that told you what my heart meant…

These foolish things remind me of you—”

Somewhere down the alley that runs behind our back apartment, there is a voice teacher who gives lessons in his home, and in the afternoon one might catch a gorgeous line of opera, or part of a classic show tune. Every year just before Christmas, the voice teacher has his students over for a party, and my wife and I will sit by the window in the evening, listening to the animated buzz of party conversation, then the sound of students and teacher singing together around the piano.

We have no way of knowing just where the music is coming from; there are four or five apartment houses down the alley. Nor would we ever want to be invited, or even to look in on the party. It would only be bound to disappoint. It’s much better this way—evoking at once all of the best holiday parties we have ever been to, or imagined, or seen in the movies, just by ear alone.

Or take the space where I am writing this. It is a little room, that faces on the fifth floor of the small inner courtyard of my building. It is a good space for a writer. There is not much to see—only brick walls, a small patch of sky, and other windows with the shades perpetually drawn for privacy.

But in the evening I can hear a whole hive of activity, all around me. People preparing or clearing away dinner, scraping plates or lighting stoves. Calling to children to take their baths, or do their homework. Laughing, and speaking in English, Spanish, Mandarin, Creole French, and other tongues I do not recognize. Somewhere there is even a man ringing small bells while he chants Buddhist prayers.

This is, I think, the great, redeeming quality of city life, what makes it worthwhile living here, despite all the thoughtless depradations of bikers and truckers, and radio blasters. It is the rare opportunity to both live in the world, and yet remain as distant from it as one needs to be at any given moment. The chance to listen, and yet be still.

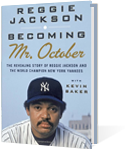

Kevin Baker is working on a historical novel, Strivers Row, which is set in Harlem in the 1940s.

© Copyright The New York Times